Red mites on hens: how can you get rid of them for good?

Contents: What is the poultry red mite? | How can you tell if there are red mites in your chicken coop? | What environment is conducive to the development of red mites? | What are the signs that suggest a chicken is infected with red mites? | How can you control red mites? | 9 best practices

A veritable scourge of the henhouse, poultry red mites bite your chickens and are quick to multiply. The typical signs of a poultry red mite attack in your henhouse should alert you. Francodex explains how to identify these haematophagous mites and get rid of them permanently.

What is the poultry red mite?

Poultry red mites (Dermanyssus Gallinae) feed on blood by biting their hosts with their specialised mouthparts to pierce the skin.

Measuring between 0.5 and 1mm, but visible to the naked eye, the red mite is flat and oval, and white to greyish in colour before feeding, turning red after consuming blood.

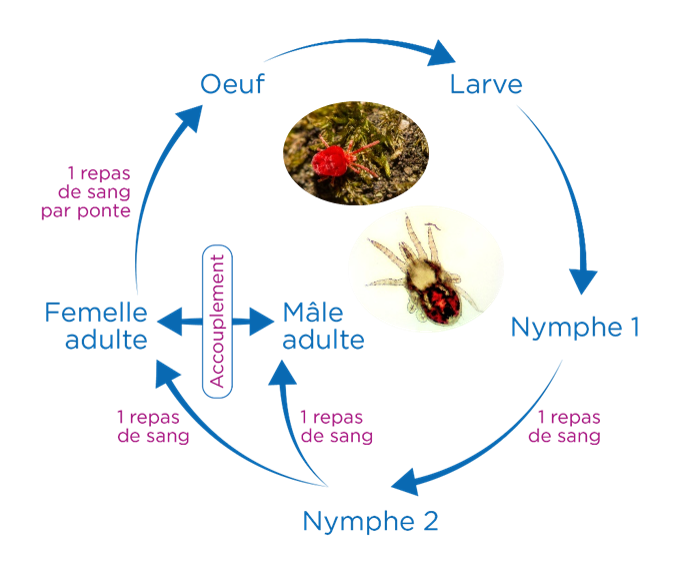

Larvae, nymphs, adult females: at every stage of their development, red mites need to feed in order to move up a stage and reproduce.

Red mites have a rapid reproductive cycle, especially in summer: females can lay up to 300 eggs a week in cracks in chicken coops, perches or nesting boxes.

In three days, the eggs hatch into larvae, which turn into nymphs and then adults in less than a week. Adults live for around two months.

THE LIFE CYCLE OF THE POULTRY RED MITE

🐔 Red mite bites in humans: Yes, red mites can bite humans, although they prefer birds. The bite causes itching and skin irritation, and in some cases allergic reactions even. However, red mites do not stay on humans and cannot live very long without their avian host.

Red mites are a common and difficult problem to deal with, whether on a factory farm or in a backyard coop with a few hens.

How can you tell if there are red mites in your chicken coop?

To check whether there are red mites in a henhouse, inspect dark areas, perches, nests, cracks and the hens themselves at night with a torch.

Signs that should alert you to the possible presence of red mites include:

- restless chickens,

- missing feathers,

- skin lesions caused by the bites and scratching,

- traces of blood on the feathers,

- black faeces, that look like trails of pepper, reveal their presence.

💡 Useful tip! Use double-sided tape to catch and examine suspected mites.

What environment is conducive to the development of red mites?

Red mites thrive in warm, humid environments (between 20 and 30°C with 70-90% humidity). Poorly ventilated hen houses, with a lot of cracks and dark corners, offer the perfect conditions for them to multiply. They come out of their hiding places just long enough to bite your chickens, before hiding away again. They are hardy when in a suitable environment, and can go several months without feeding in cold weather.

In addition, perches, nests and litter that is not properly cared for provide perfect hiding places for these mites.

Insufficient cleaning and inadequate management of organic debris encourage the proliferation of red mites.

🐦 So where do red mites come from? Red mites come from wild birds, garden birds, infested hens, contaminated equipment or neighbouring chicken coops. They find new hosts through direct or indirect contact.

What are the signs that suggest a chicken is infected with red mites?

A hen bitten by red mites shows symptoms such as:

- nervous, agitated behaviour and frequent scratching,

- pale crest and wattles (sign of anaemia),

- fewer eggs,

- weakness.

Your chickens can be severely weakened if you don’t act quickly to control the proliferation of red mites.

What’s more, an anaemic hen suffers a drop in its immune defences, making it more vulnerable to infection and disease. Red mites can also transmit salmonella.

🐔 Other mites can attack hens too: Knemidocoptes mutans, for example, is responsible for causing scaly leg mite in your hens. Francodex’s solution is GAL O PAT, a product for you to mix with the litter in the chicken coop to ensure your poultry’s well-being. Another option is GAL O CADE, which is applied directly to unfeathered parts of your hens.

If your chickens are infested with red mites and you have noticed the symptoms, consult your vet as soon as possible.

How can you control red mites?

There are two stages in the fight against red mites:

- treating the animal (or helping it to fight back);

- cleaning the environment to eradicate the red mites from the henhouse.

Treating the chickens

There are two ways of preventing red mites from infesting your henhouse:

- use insect repellent* products, such as Francodex insect repellent pipettes to combat fleas, red mites and other biting insects. These are applied directly to the animal and repel the parasites. Another solution is Francodex dimethicone anti-parasite spray, which acts mechanically on external parasites and can be used as soon as mites are seen on the chicken;

- administer feed supplements such as Francodex Pounet, which contains thyme and tansy (one maxi-bottle of Pounet for 20 hens). This product supports your chickens’ metabolism in the event of a red mite infestation. This product is popular with many farmers and has no impact on egg quality.

*Biocide class TP19: biocidal products must be used with care. Always read the label and product information before use.

⚠️ Please note that these products are not medicines. If the infestation or symptoms persist, consult a vet as soon as possible to contain the proliferation and save your hens. An animal health expert will be able to advise you on the right treatment for laying hens, which have very specific needs.

🐔 Androlis mites, natural predators of red mites: biological control is a natural and effective solution for combating red mites on chickens. Androlis mites are completely harmless to your hens, but devour red mites. For best results, make sure you regularly introduce enough predators into your henhouse.

Finally, during or after treatment against red mites, supplement your chickens’ mineral intake with Francodex Oligo-Energy.

Treating the chickens’ environment

To treat your chicken coop, perches and nesting boxes against poultry red mites, Francodex has diatomaceous earth-based products**that you mix with their litter.

Diatomaceous earth has a lasting mechanical insecticidal effect. It comprises fossilised microalgae, whose skeletons consist primarily of silica (a mineral resembling small glass crystals). The microalgae act on the mites by injuring them and causing them to dehydrate.

It can be used both indoors and outdoors. However, when it is wet, it is no longer active, but it regains its properties once dry.

Diatomaceous earth insecticides should be handled with care, using protective equipment (gloves and masks) and following the instructions for use on the packaging. Reapply once the product has been dispersed by the hens.

To treat the chickens’ environment and all the occupants of the henhouse, Ecto Choc Parasites Duo spray neutralises crawling and flying insects by direct contact, without chemical insecticides and using only 100% natural ingredients. Use it before cleaning the henhouse to remove any mites present without them escaping.

**Biocide class TP18: before use, ensure it is essential to do so, especially in areas frequented by the general public. Whenever possible, use alternative methods and products that present the lowest risk to human and animal health and to the environment.

9 good practices to prevent red mites from appearing in your chicken coop

To prevent the appearance of red mites in a henhouse, rigorous cleaning and attention to detail regarding the structure are essential.

Follow these 9 tips for a henhouse free from external parasites:

- Clean your henhouse regularly by removing droppings, feathers and organic debris.

- Use effective, natural cleaning products (black soap, which must be thoroughly rinsed, a spray made with white vinegar (1:1 solution) which should be left to dry, etc.) to disinfect all surfaces, including roosts and nests.

- Seal any cracks and nooks and crannies where red mites could hide.

- Ensure the henhouse is built in such a way as to reduce the number of potential hiding places for parasites.

- Use smooth, easy-to-clean materials for perches and nests (plastic rather than wood). Avoid porous materials and complicated structures, as these can harbour red mites;

- Limit your hens' contact with wild birds, which are often carriers of red mites. You can install protective netting to keep wild birds out of the henhouse and runs.

- Quarantine new hens before introducing them into the henhouse.

- Maintain good ventilation to reduce humidity.

- Monitor your hens and facilities regularly to detect any infestation quickly and take immediate action.

By combining these cleaning, structural and contact management practices, you can considerably reduce the risk of red mite infestation in your henhouse.

Article written with the assistance of

Dr Stéphanie Padiolleau, veterinary surgeon